Do Women’s Lives Matter?

A Call for Over-the-Counter HPV Sperm Testing

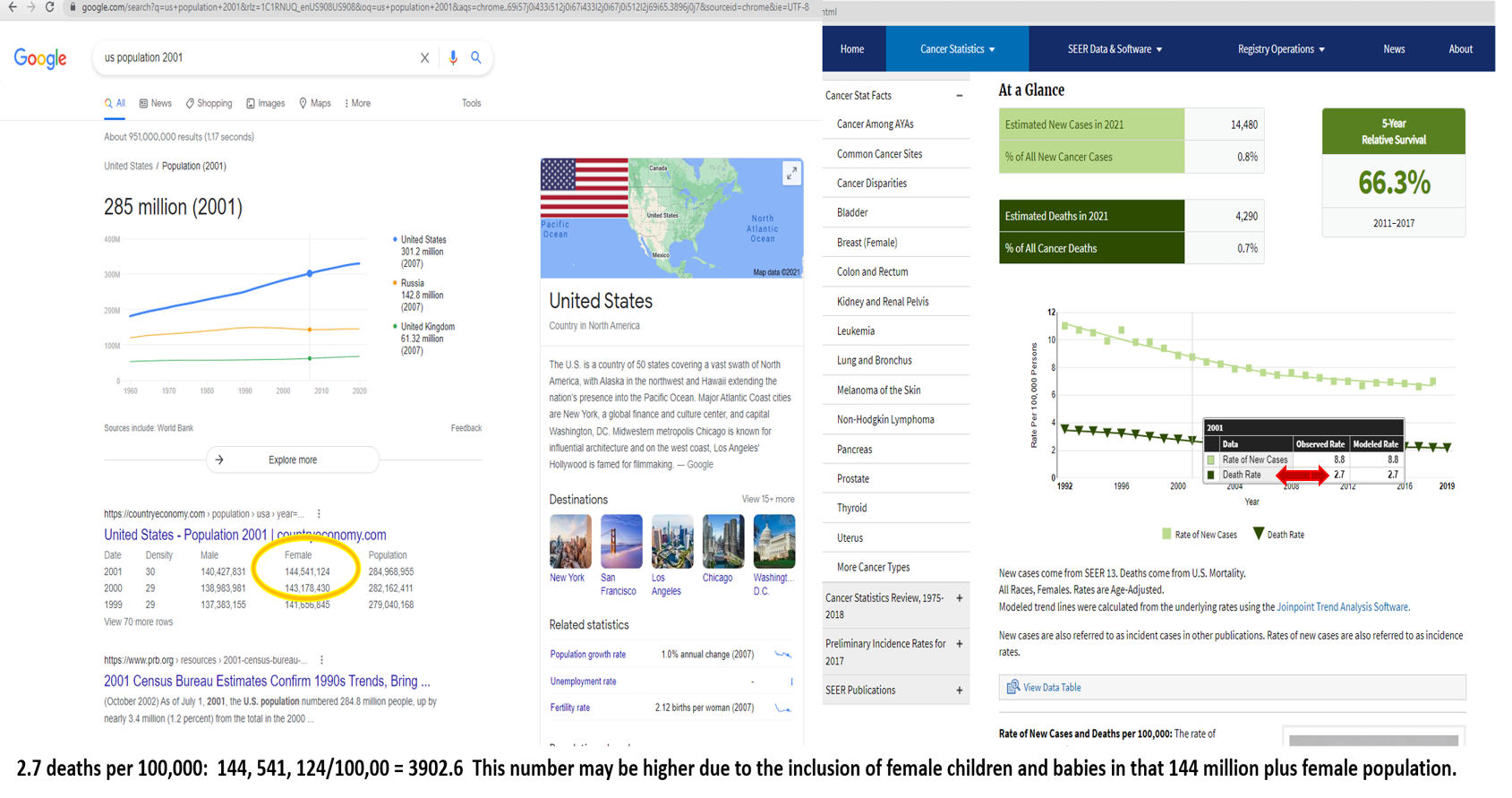

According to the World Health Organization, 570,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2018, and 311,000 died from it that same year. In January 2021, The Global Cancer Observatory reported that worldwide, there were 604,127 new cases of cervical cancer that resulted in 341,831 deaths in 2020. Approximately 1.3% (4,290) of those worldwide deaths were in the United States. All of these women are dying from the same disease that according to the CDC, is nearly 100% preventable; and there’s a simple solution, yet no one is talking about it. Why is that? Don’t women’s lives matter?

Nearly 4,300 deaths among more than 300 million people may not seem like that many (unless of course, you or someone you love happen to be one of them), but let’s remember: we lost an estimated 2,977 people (75% male) on 9/11/2001 and we remember them every year (and rightfully so). Recently, there was an ABC 9/11 television special, during which the voice of a woman announced at the beginning, that we were about to revisit the children of the men who died on 9/11, and speak to their wives. But what about the more than 700 women who died at the towers that day? Didn’t any of them have children? Didn’t any of them they have husbands or other family members who missed them as well; surviving loved ones whom we could visit 20 years later? It certainly begs the question: Do women’s lives matter; even to other women? In addition to the hundreds of women who died at the towers, we also lost approximately 3,902 women that same year to cervical cancer; a tragedy that collectively, we never hear about.

Fortunately, what happened to our nation 20 years ago has never been repeated. Yet we have continued to lose thousands of women every year since long before 2001, and the number grows in silence, with each passing year. As the number of cases and deaths have continued to increase over the past 20 years, it would be a conservative estimation to say that since the year 2000, nearly 5 million women have died from a disease that experts say is nearly 100% preventable, and that worldwide, more than half that number (another 2.9 million) will die from cervical cancer within the next five years alone, including 37,700 in the United States.

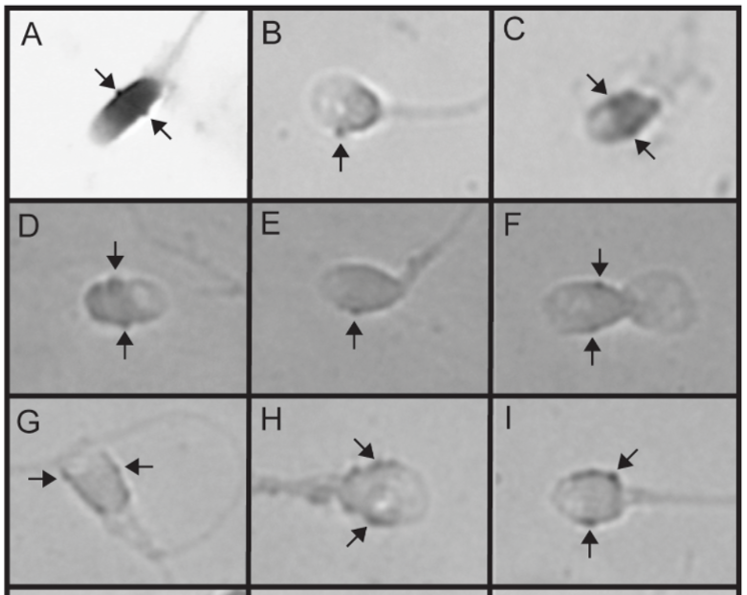

Although HPV affects both males and females, overall, it appears to have a much greater negative impact on women, with women under the age of 25 at the highest risk (Rousseau et al., 2001). Yet studies indicate that the women who are at the highest risk are also less likely to get screened. It is frequently stated that HPV is a common, sexually transmitted infection. What is stated much less often, is the indication that not only are human males shown to be reservoirs and vectors of HPV (Kombe et al., 2020), meaning that they carry it and they spread it; but that it is their spermatozoa specifically that carries HPV, and is capable of delivering it straight into the female egg at the moment of fertilization (Zacharis et al., 2018).

HPV attaches itself to the head of sperm (Foresta et al., 2011) and when an HPV infected sperm cell fertilizes an egg, the HPV can negatively affect the developing blastocyst (Zacharis et al.). In other words, a sperm cell that is infected with HPV is known to cause so much damage to the DNA of the developing fetus, that it can cause a woman to spontaneously abort or miscarry. More than 200 types of HPV have been identified (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021), and most do not cause cancer. This may help to explain why males, who carry HPV, are not as negatively impacted by HPV, unless they are prone to engage intimately with other males who may carry a different strain of cancer-causing HPV than they themselves, already do.

*It is important to note that while most HPV types naturally clear the female body within two years, some HPV types can linger in the body for years or decades before making themselves known, in the form of cancer (CDC, 2014). This uncommonly known fact, combined with an under developed immune system is why although women under the age of 25 are not likely to have cervical cancer, if sexually active, they are the most vulnerable to becoming infected with a cancer-causing strain of HPV (Wang et al., 2021) which can lead to cervical cancer years later, when they are in the prime of their lives. However, although women under the age of 25 are the most vulnerable, regardless of age, all women who have ever been directly or indirectly sexually active with a male are at risk. Because cancer-causing HPV can linger in the body for decades before developing into cancer, getting tested regularly includes women in their 70s and beyond, who may or may not be sexually active, but likely have weakened immune systems due to age. As mentioned earlier, in addition to cancer, HPV types 16 and 18 have been shown to cause sperm DNA fragmentation (Boeri et al. 2019), which can lead to spontaneous abortions (Syrjänen, 2010). As a side note, interestingly, spontaneous abortions have also been shown to be a marker for premature death in women, primarily as a result of cardiovascular disease (Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, if you or someone you care about has had multiple miscarriages, then please encourage her to professionally monitor her heart health.

HPV types 6 and 16 found attached to sperm, between the arrows.

Screenings for women over the age of 21 are recommended every three years, in an effort to catch abnormal cervix cells early (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2021). However, a study conducted in 2012 and published by the Journal of Women’s Health and the National Institutes of Health, concluded that to get cervical cancer under control, instead of Pap Smear screenings, HPV testing of sperm is needed.

Although not yet available to the public, technology exists, packaged in kits and marketed to science labs, that can easily test spermatozoafor a variety of HPV types. These spermatozoa test kits should be modified, if necessary, for home use, and sold over-the-counter to the general public, in an effort to stamp out cervical cancer, and to reduce spontaneous abortions as well. Whether male or female, awareness of a partner’s HPV type could go a long way towards eliminating all cancers known to be caused by HPV. These cancers include but are not limited to cervical, penile, throat, and anal cancers.

Women make up 51% of the U.S. population. Collectively, we have a powerful voice. But have we been divided and conquered by race, culture, or right to choose? We risk our lives when we go through the process of pregnancy. We risk our lives if we choose to end a pregnancy. We risk our lives when we choose to give birth. And now we know that we even risk our lives when we simply have sex; whether by choice or by force. Imagine a modern, female child who grows up and does everything she may have been taught to do: she goes to college, starts a career or business, she gets married and has children; only to die at age 40 from cervical cancer, because she didn’t realize that for years, the only man she has ever had sex with, has been regularly infecting her with #16 HPV. Despite the lack of collected evidence at the time of diagnosis, it is believed that more than 90% of women get cervical cancer as a result of HPV. Don’t we have a right to know if our male partners are infecting and re-infecting us again, and again and again, with a cancer-causing strain of HPV, every time we are intimate with them? Shouldn’t we be “allowed” to minimize our risks as much as possible? Only when enough of us demand it, will the companies who already manufacture HPV sperm testing kits for laboratory use, see the potential, and make these kits available to the general public. Or maybe, a few female scientists and entrepreneurs will work together to make over-the-counter HPV sperm testing kits available to everyone within the next year or two. Collectively, it is certainly within our ability to accomplish this.

Take a walk through the aisles of any pharmacy and choose a pregnancy test from the shelf; in 1975. No, that couldn’t happen back then. Today, there are numerous home pregnancy tests to choose from. But in 1975, there were exactly zero. This very handy and important “fortune teller” didn’t hit the shelves until 1977. In what year will over-the-counter sperm testing kits hit the shelves? That’s truly up to you. We may not agree on whether a woman has a right to choose to give birth; but can we at least agree that she has a right to know if the man she’s about to give herself to, is not only carrying a cancer-causing strain of HPV, but also may be carrying a strain that could possibly cause her to experience the physical and emotional agony of miscarriage, should she happen to become pregnant? Regardless of race, religion, culture, or economic background, we all have one, most important thing that binds us all together: that which makes us all women, as well as prey for cervical cancer-causing HPV. Therefore, let us unite, and end this game of Russian roulette we play, every time we have sex with our male partners, by demanding (or developing for ourselves) over-the-counter HPV sperm testing kits; and demonstrating that indeed, women’s lives do matter…at least…to us!

Defective sperm, whether infected with HPV or deformed

in some other way, can affect your pregnancy outcome as well as the long-term health of your baby.

It has been nearly 10 years since that study mentioned above, concluded that HPV sperm testing is needed in order to get cervical cancer under control. Since that time, millions of women around the world have died unnecessarily; including tens of thousands of women right here in the U.S. But is it really that serious? Well I suppose that depends on your perspective. If you are a male, then although you may be indirectly affected by cervical cancer through the loss of a mother, sister, or spouse, you yourself will never die from cervical cancer. And for men to die of penile cancer is practically unheard of. In 2018, the Global Cancer Observatory reported that worldwide, there were 93,850 new cases of penile cancer and 15% of them, 15,138, resulted in death. Comparatively, that same year, there were 569, 847 new cases of cervical cancer, and 54% of them, 311, 365 resulted in death. As for women, not every woman who gets infected with a cancer-causing strain of HPV, gets cancer. In fact, cervical cancer is considered to be fairly rare. But then, it is also “fairly rare” for a person to die of Covid-19. That is, although Covid-19 is highly contagious, and massive numbers of people have been infected, even before the vaccine was released for use, only 1.7% of all the people who got the virus, died from it.

In 2020, approximately 13,000 women in the United States were diagnosed with cervical cancer, and 4,290 are reported to have died from it. That’s 33%. Thirty-three percent of all women who got cervical cancer in the United States in 2020; died from it. And if we include worldwide numbers, we find that more than half (54%) of all women who got cervical cancer, died from it. More women died in 2020 than in 2019, and more are expected to die in 2021, than in 2020. Every year it seems, the number gets higher; yet according to the CDC, cancers caused by HPV are the only known cancers that are preventable. So, although it may be “fairly rare” for a woman to get cervical cancer, if she does get it, she has a 1-in-3 chance of dying if she lives in the U.S., and worldwide, she has more than 1-out of 2 chances of dying from a disease that could have been prevented.

How can cervical cancer be prevented?

First, parents: choose your teen aged babysitters wisely. A sexually active babysitter who quickly shoos a child out of the room after being caught with his/her boyfriend, can pass HPV on to a child through skin to skin contact. The same is true of course, for parents as well. Yes, parents too, can unwittingly pass on HPV to their children through skin on skin contact, if they are not careful to clean themselves properly before touching a child after having sex. Approximately 10% of virgin girls have been found to be infected with HPV, quite possibly for these reasons.

Second, before you have sex for the first time, make sure your immune system is fully developed and strong. This does not typically happen in the average human until approximately age 25. Again, this is the primary reason that women under the age of 25 are at the highest risk for developing cervical cancer in their late 20s, 30s, and 40s. Regardless of what the law says about the age of sexual consent, understand that due to an under developed immune system, having sex at age 16 or even 20, for example, can possibly lead to cervical cancer at age 26 or 30.

Third, regardless of age, if you are now or ever have been sexually active, then get screened regularly (every 3 years). Cancers caught early have a higher success rate for treatment and survival. Finally, there are vaccines now available. Just be sure you are aware of all the risks, as discussed in my video and e-book, Truth Talk: The Last Dating Advice You’ll Ever Need. It is also important to remember that according to an article published by the National Institutes of Health on July, 2020, Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: An updated Review, “the HPV vaccines currently being produced are based on L1-VLPs, which only provide type-restricted immunity, neglecting many other oncogenic HPV genotypes.” Additionally, the article states: “the ideal time for the best protection against HPV-related diseases is prior to HPV exposure,” meaning that if you have already had any sexual contact with a male, the vaccine is not designed to work for you.

If you have questions after reading this article, please refer to the references below, and feel free to contact me as well.